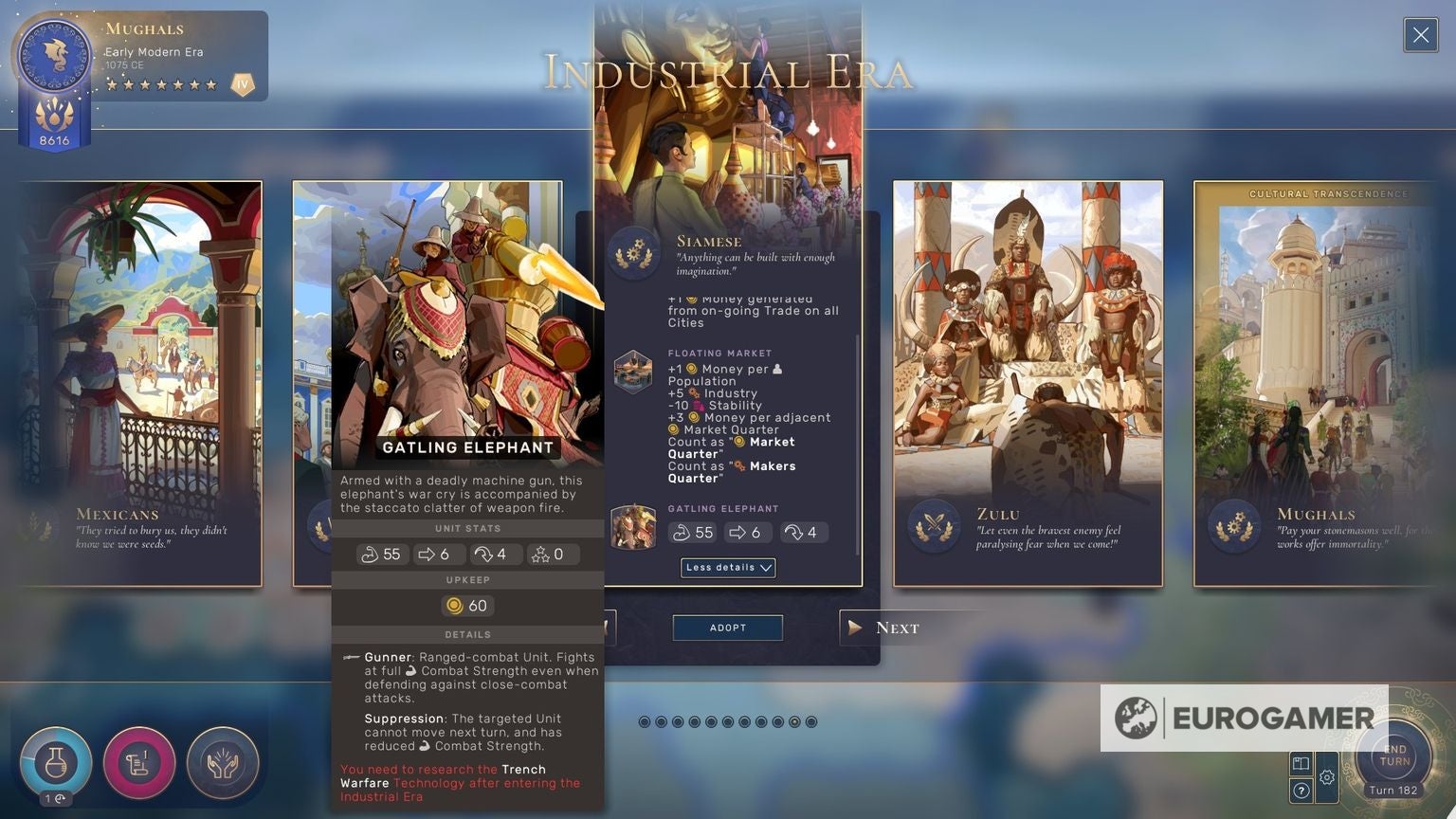

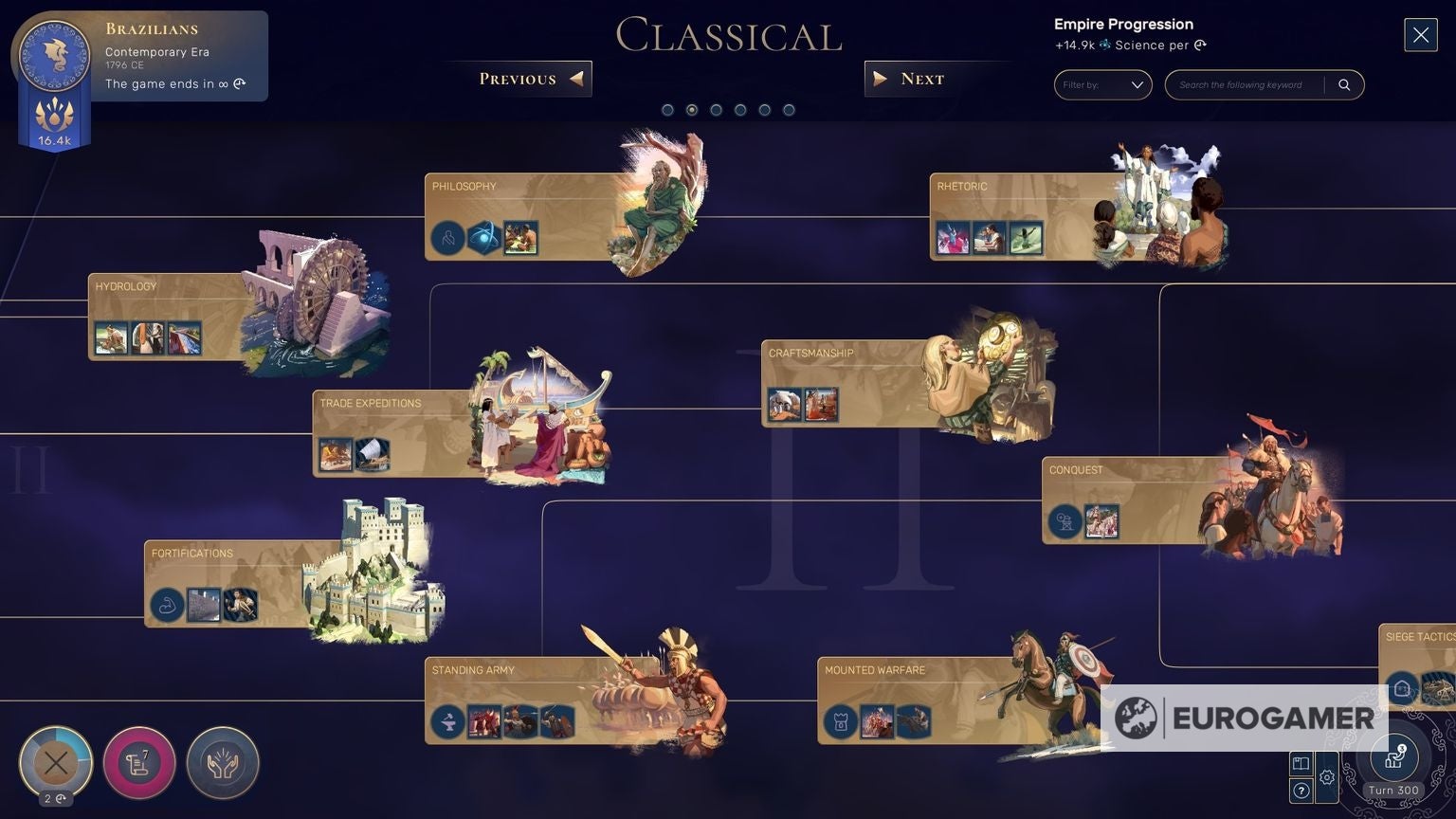

Say “ideology” too much and you start sounding like Slavoj Žižek stuck on a loop, so I’ll move on. The point is in Humankind, the new, Civilization-style historical grand strategy from Endless Legend and Space developer Amplitude, capital-I ideology is handled smartly in a kind of consequential, sliding scale system, and the considered little-I ideology of the developer is regularly felt. Amplitude has wanted to make a game like this since the day it was founded, I’m told, and a desire to do things right, whatever right may be, is front and centre. Regardless of the outcome, I love it for that. Everything else aside, Humankind plays like the most considered, most philosophical, most historically authentic (if not accurate, obviously) game of its kind. It plays like a group of very intelligent people have sat down in a room together and really thought about doing things in the most true-to-life way possible. In many ways that makes it the 4X game I’ve always wanted, the one that’s systems work in a broadly similar manner to the way they do here in the real world, that’s history is aligned, systemically, with actual humankind’s. The only problem is having played it now, I’m not sure I actually want that anymore. By far the closest parallel to Humankind is the reigning historical 4X itself, Civilization. If you’ve played Civ, especially a modern one, you can immediately play Humankind. You build cities on hexes and exploit the natural resources of the earth, you advance through a scientific tech tree, spread your religious or cultural influence, build and discover wonders, and balance all the many socio-economic strains on society as you compete against other civilisations, human or AI, to win the game. In fact, Humankind basically feels like a Civilization sequel, insofar as it’s following the formula right down to the series’ famous rule of thirds: about two thirds of Humankind is Civ through and through, and a third - basically two big things - has been reworked with a twist. The first of those big differences is the win condition. There is just one way to win a game of Humankind: fame. Fame is a numerical score, earned from achieving various in-game feats along the way, and the player with the highest score at the end of the game wins. What actually brings about the end of the game can vary: reaching a set number of turns, eliminating or vassalising all other players, completing the tech tree, launching a Mars colony, collecting all of the final era’s stars (more on that in a moment) or, interestingly, rendering the entire planet inhospitable for human life, are what bring about the final totting up. Like most aspects of Humankind, the thinking behind this is admirable. First, Amplitude wants to remove the “frustration” of someone else sneaking a win against you through a different win condition, say a culture victory, right when you were close to a science victory of your own. Second, it comes back to the desire for as much historical authenticity as possible. When we think about the most renowned civilizations, the thinking goes, many of them are no longer around - but they’re still famous, still known, if not necessarily admired, for what they did, and so that’s the way it works in Humankind. You can win a game even after you get eliminated, if by the end of the game nobody else can match the score you managed to accrue. To support this comes a system of era stars - literally gold stars you can earn, like a good little student, only you can opt to be a student of completely brutalising your enemies at war or expanding your territory with force, if that’s what you fancy. Each era, apart from the very first, has seven categories for you to earn era stars in, and three stars to be earned in each, so up 21 total per era (plus a few more for achieving certain one-off feats, like being the first to discover a natural wonder or link two cities by rail, and a special “competitive spirit” star that creates a kind of natural catch-up system to maintain balance). Each era star you get grants you a wad of fame points to add to your score, so generally the more you collect each era the better - but that comes with a large and very clever caveat. You get more fame for stars of the same category as your current culture, which is where Humankind’s second big departure from Civilization - and most other grand strategies - comes in. Rather than choosing a single culture or leader at the beginning of the game, like Genghis Khan or the Greeks, everyone starts out with the same blank slate: a single nomadic tribe, that slowly grows as you explore. When you advance to a new era, you then choose your culture for that era, and alongside the usual things like a unique unit, passive ability and building, comes a specialty. So, the Mongols’ specialty is combat, which means when you earn a combat era star for defeating a certain number of enemy units, you get more fame than you would for other era stars like science ones. Again, it comes down to authenticity, the philosophy of doing things in Humankind in a way that represents real life. Humans, broadly speaking, didn’t start out as distinct cultures like Romans and the British Empire, we started as small nomadic tribes and we adapted along the way, building societies and cultures around the many circumstances of life. So it goes, on paper pretty ingeniously, in Humankind. You might start out prioritising your fighting capabilities because you settled right by some angry independent tribes, or an aggressive rival culture, and so your first culture of choice might be a combat-oriented one, granting you bonuses of that kind and more fame for doing that combat well. And even within that specialism there are nuances - some militarist cultures have more defensive bonuses than offensive, and vice versa. Higher level play then requires you to think more proactively about how your choice of culture affects your fame, rather than just reacting to the world around you. Doing well militarily, for instance, might have meant you set yourself up with a city full of industrial districts (makers quarters, as they’re known in Humankind) to help pump out warriors fast. Nearby enemies vanquished, that sets you up rather nicely for an era of building, so picking a “builder” culture next, rewarding you for simply constructing more districts, would be a smart move. And you might think further ahead than that, building a load of science districts (research quarters) to earn builder stars during your builder era then picking a science specialist for the following one, capitalising again. There’s also a couple of clever trade-offs that come with the system. You just need seven of the 21 available era stars to advance to the next era, and cultures are first-come first-served, so you’re incentivised to rush to the next one before you lose out. But, once you move on you can’t collect any remaining stars from the previous era, so the longer you stay in an era, the more stars - and thus fame - you can collect overall. There’s also the option to “transcend” your culture to the next one, which means keeping everything the same and missing out on shiny new units or buildings, but getting a 10 per cent boost to all the fame you generate. So, you have a more true-to-life start to the game, and a more true-to-life system of cultures for advancing through it, and a more true-to-life way of actually winning, victory as memorability or renown. Put it all together and you have a remarkably clever system, in theory. In theory. In practice, there are some snags. Alongside the authenticity of it, one of the stated goals for having you move between cultures as you progress is variety. There are millions of combinations, quite literally, and so the theory is that no two games will ever be the same. But actually, adapting from one specialty to another, as the circumstances demand, means the game can turn into something of a blur, rushing you towards that soupy late-game state you find in similar grand strategies, where you might have one or two outstanding specialties but really need to be doing a bit of everything for them to work anyway - money to pay for your troops, science to keep them advanced, industry to build them fast, food to supply the population, and so on. The endgame everything-bagel state is far and away the worst part of grand strategy games as a result of this, requiring busywork and attention in every direction, and so anything that makes games feel more like that rather than less is a problem. More than that though, an oft-forgotten part of what makes a truly great strategy game of any kind, especially the grand ones, is role-playing. This is, really, the entire point of the wider genre: be it Stellaris or Civ or anything else, you play these games in order to sit back with a character-appropriate drink and assume the role of blustering commander-in-chief, or omnipotent demi-god, or shrewd technocrat, and this is hard to do when you’re actually only a technocrat for a couple dozen turns before the next era comes around. You’ll quickly find yourself rushing through roles like a one-man-theatre, shoving a lab coat over one arm of your military fatigues before you’ve whipped off the builder’s hardhat. You can stay as one culture throughout, admittedly, through the transcendence option, but it will take some considerable skill to win a game that way, especially against militaristic foes with unique tanks rolling in or special fighter jets overhead, and the implication is very much for you to chop and change as you go. Similarly, the victory conditions play into that. I pick Genghis Khan or the Imperial Space Slugs or whoever because I want to go for a military victory and play that way from the off, with a bit of adaptation where necessary, and that clarity of purpose is what separates one game from the next. And the surprise of an enemy pipping me to the post is, in a way, the point. The end of a good grand strategy is tense, you holding off an enemy horde while you try to rush through the construction of a final spaceport, or buy up whatever artefacts you can find to steal some last-minute tourists from someone on the verge of a cultural win. Focusing on era stars, which are undymanic - as in once you get one you can’t lose it - means the systems are largely quite insular, even if you can technically use plenty of inter-player tools, like influence-bombing a territory to make it yours or just ploughing through a city with your army to reduce the population of someone going for an agrarian star, but that’s less sophisticated than you’d hope for a game of this kind. Finally, there is just a lingering sense that Humankind feels a tiny bit flat. It’s a beautifully presented game in a vacuum, with a clean and mostly well-explained UI (although there are a few bits of awkward copy, and the tutorial never actually explains how building a city works, just that it can be done by converting outposts, which seems like an oversight, but these are very forgivable in the early days of a launch). But there’s a missing spark, a missing celebration, in a way, that’s quite stark when compared to its peers. There’s no fanfare at all for unlocking new technologies - a good, if slightly sarky narrator only popping up on occasion - and the soundtrack again is good but a little unspectacular, no Baba Yetu or Creation and Beyond. These are games about all of humanity, about the wonders and horrors and dreams and nightmares of all that humans can do. There’s an obligation on the historical 4X, above all other games, to inspire fear and awe, and Humankind can often appear to think mere appreciation is enough. It’s a crying shame, because the package as a whole is great. The ideology system - little-I - is a highlight, a series of left-right axes that your civilisation is nudged between according to civics you enact and decisions you make on pop-up narrative events. The further you go towards one ideology’s end, like authoritarianism, say, the greater the related bonus and the greater the hit to your overall stability, or how likely your cities are to revolt. It makes sense! A lot of sense, as so much of this game does, filtering through clever societal commentary through mechanical nuance, the strategy game’s golden ideal. Religion is very simple and somewhat unplugged from other mechanics - you get to add a new tenet when you hit a new follower threshold, you don’t get them if you get converted - but it’s effective. Diplomacy is mostly functional, which is about as good as diplomacy’s ever been in a video game, so no worries there. And combat, in particular, is a delight. Humankind’s got Civ beat there, and plenty others. It’s like a lighter version of something like Age of Wonders, where an overworld clash is zoomed in to a simplified XCOM-style tactical battle, taking place over a few hexes of battlefield. There’s good nuance to it - elevation and sightlines are crucial, as is positioning and, at higher levels of play, a good understanding of what all the many units are capable of. It works well, is quick and breezy and deep if you want it to be. In many ways it reflects much of Humankind as a game: a lighter touch than some others in the genre maybe, more accessible once you get past the typical new-strategy-game fog, and clean, elegant, thoroughly thought-out. The problem is the thinking-out is where the problems arise, too. It might be trite to say, but Humankind seems to have been made on an ideology slider of its own. Playfulness on one end, authenticity on the other. Too much towards either end of the axis and you lose stability, lose the fine balance of what makes a great historical strategy sing, and for the moment Humankind’s just a smidge too far to the latter. It’s missing a little magic, the wildcard element of a Great Person, the human touch of named, well-renowned faction leaders as opposed to your custom, but otherwise mannequin-esque avatar. Or those villainous, caricatured opponents that stick in the memory, instead of whoever it is behind “the green faction”, who’s name changes every couple dozen turns. Still. Amplitude has promised to support Humankind for some time, and these games inevitably change over the months and years after launch - especially ones built on open development like this. Hopefully an opportunity might pop up that lets them nudge things just a little further towards the fun, because if the studio does manage to strike the right balance further down the line, they’ll still be onto a winner.